- Sheep 201 Index

- Other web sites

Dairy Sheep Basics

Sheep (and goats) have been milked for thousands of years, probably before any other animal. The dairy sheep industry is highly developed in many countries, especially in and around the Mediterranean Sea. In the United States, sheep dairying is a small part of a small industry. Most US sheep dairies are located in the Upper Midwest and New England states. At the same time, there are sheep dairies in most states, and there is potential for expansion of the industry, as the majority of cheese made from sheep milk is imported.

In a dairy sheep operation, the sheep are usually triple-purpose, but the emphasis is on milk production. Management decisions are usually made to maximize milk production. At the same time, lamb sales can contribute a significant amount of income to the dairy sheep enterprise, especially if lamb prices are high or if breeding stock can be sold for premium prices. Wool receipts are usually negligible unless fleeces are direct marketed or value is added to the clip. Sheep dairying is sometimes combined with agritourism.

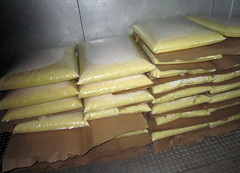

Sheep milk is superior to the milk from goats and cows for cheese-making. It is much richer, containing a higher percentage of fat, solids, and protein. For this reason, sheep milk gives a much higher cheese yield than the milk from cows or goats. Yogurt and ice cream are also commonly made from sheep milk. Sheep milk is rarely consumed as fluid milk.Though fresh milk is preferred, sheep milk can be frozen for up to a year without losing its cheese-making qualities. The freezing qualities of sheep milk allow producers to manage their milk supply easier. They can wait until they have enough milk to ship to a processor. The milk can be shipped on pallets to distant processors. It is usually frozen into 40-lb. bags.

Cow Goat Sheep Source: The nutritional value of sheep milk by George F. W. Haenlein

Breeds

Theoretically, any breed of sheep can be milked, but it is unlikely that it would be profitable to milk traditional meat (wooled or hair) or wool breeds. In the United States, there are three dairy sheep breeds: East Friesian, Lacaune, and Awassi. It is most common to cross the Lacaune with the East Friesian.

The East Friesian is the most numerous dairy sheep breed in the US. Lacaune sheep are available in lesser numbers and have a limited gene pool, though the industry was been importing semen (from France) to freshen the genetics. In 2013, the Awassi was introduced to the US via embryos and semen. Crossing the Awassi with the East Friesian yields another (recognized) breed of dairy sheep called the Assaf. The British Milk sheep, currently raised in Canada, may eventually make its way into the US.

East Friesian

The East Friesian is considered to be the heaviest milking breed of sheep in the world. It is analogous to the Holstein cow. In fact, the East Friesian was developed in the same region as the Holstein, the Friesland area of Germany and Holland. The average milk production of the East Friesian can exceed 1,000 lbs. of milk during a 220 to 240-day lactation.East Friesians are also efficient lamb producers. Mature ewes average more than two lambs per lambing. Even yearling ewes are capable of producing 200 percent lamb crops. East Friesians are docile and adapt well to intensive parlor milking systems. They do not fare well in hot climates and are not suitable for extensive management systems. Lambs are prone to pneumonia.

Lacaune

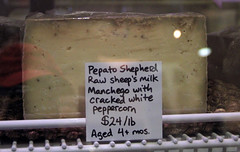

The Lacaune is a French breed of dairy sheep. In France, the Lacaune breed has been rigorously selected for improved milk production. At one time, annual genetic improvement for milk yield was estimated to be 2.4 percent. The Lacaune is the breed used to produce France's famous Roquefort cheese. In fact, it is the only breed whose milk can be used to make Roquefort cheese.

As compared to the East Friesian, the Lacaune is a hardier breed of dairy sheep. They give birth to fewer lambs and produce less milk, but their milk is higher in fat and protein, giving better cheese yields. The Lacaune has very little wool, on its head, legs, and a good portion of its belly is bare.Awassi

The Awassi is a fat-tailed sheep that originated in the Middle East. The improved Awassi is one of the heaviest milk producing breeds in the world, second only to the East Friesian. Awassis are a hardy breed, having evolved under arid, nomadic conditions. They have brown faces and legs and produce carpet wool. Males are horned whereas ewes are usually polled.Icelandic

The Icelandic breed is sometimes raised for dairy purposes. In Iceland, it was historically used for milking. While Icelandics will produce less milk than the specialized dairy breeds, they are hardier and known for having good udder conformation. For the small farm cheese processor, Icelandics may be a good choice. They may also be better-suited to grass-based production systems than the specialized dairy breeds which would have much higher nutritional requirements.British Milk Sheep

The British Milk Sheep is a cross between many breeds (especially East Friesian), with heavy selection for milk production. They are considered to be a dual-purpose breed (meat + dairy) and are the most prolific breed in Great Britain.

Upgrading

With only a few breeds to choose from and a small industry, the acquisition of good quality breeding stock can be challenging. Both cost and availability can be limiting factors to developing a profitable sheep dairy. A meat breed flock can be graded up to a dairy flock.Dorsets and Polypays have usually been the meat breeds of choice for grading up to dairy sheep. The F1's (first crosses) can be milked, but ewes with a higher percentage of dairy breeding will substantially increase milk yield. Some meat sheep producers have infused dairy genetics into their flocks to increase milk production.

Conventional breeds Conventional x dairy Dairy breeds Source: Wisconsin Dairy Cooperative (2008) At one point, there was some interest in creating a dairy hair sheep. The Spooner Ag Research Station in Wisconsin (now closed) evaluated Katahdin x Lacaune crosses for sheep dairying. Their conclusion was that Lacaune x Katahdin crossbred ewes would be acceptable for low-input, easy-care systems where maximum milk production is not the goal. The cross may also be suitable for producers in the South and Southeast, where heat tolerance and parasite resistance are of greater importance and where more extensive production systes may be employed.

Breeding

The attrition rate of dairy ewes is usually much higher than it is for ewes that are raised for meat and/or fiber production. Dairy ewes are usually intensively managed for high milk production. They “work” harder than conventional sheep. Spoiled udders are a common cause of culling. It is best to select replacement stock from the younger ewes in the flock, as they should have the best genetics.About 30 percent of the flock should be bred to produce replacement stock. These should be the best ewes in the flock. The remainder of the flock can be bred to a terminal sire breed, such as Suffolk, Hampshire, or Texel, to produce crossbred market lambs. Not only will the crossbred lambs grow faster and produce superior carcasses, but their vigor will likely be superior to the pure dairy lambs.

Dairy sheep, especially East Friesians, are not known for their hardiness. Their lambs are prone to pneumonia. All other things being equal, hybrid vigor (crossbreeding) is the best way to improve lamb vigor and survivability. According to various studies, Texel-sired lambs have higher survival rates than Suffolk-sired lambs. They may also be more resistant to internal parasites; an important factor if the crossbred lambs will be grazed. There is emerging evidence that lambs that are more resistant to worms (have lower fecal egg counts) have higher surivability.

Management

Winter lambing is usually most common in commercial sheep dairies. While there are some disadvantages to winter lambing, it will result in the longest lactation period, thus the most milk being produced.

Lower costs are usually associated with spring lambing, but the lactation period will be shorter, as milk production decreases rapidly as fall approaches and day length begins to decrease. Year-round milking would require two groups of ewes, and spring breeding may require hormone or light manipulation of the ewe's reproductive cycle. Freezing milk might be a better way to get around the seasonality of sheep breeding, though frozen milk is less desirable than fresh milk.

Dairy ewes should be sheared prior to lambing. East Friesian ewes seem to have particularly thick fleeces. A short fleece is more desirable, contributing to a more sanitary milking environment. It is also advisable to dock dairy ewes, as a long tail (even the East Friesian's rat-tail) does not make for hygienic milking conditions.

The health management of dairy ewes is similar to other types of sheep. Ewes should be vaccinated for clostridial diseases approximately four to six weeks prior to lambing. Lambs should receive two vaccinations for clostridial diseases. The need for additional vaccinations will depend upon the flock's disease history and risk.

Deworming should be done on an as-need basis only, based on the observation of clinical signs such as anemia, bottle jaw, poor body condition, and dagginess. Particular attention must be paid to the milk withdrawal periods for the various anthelmintics. Morantel tartrate (Rumatel) is the only dewormer with no withdrawal period for dairy animals (cows and goats). However, it is not labeled for sheep. A veterinary prescription and valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship (VCPR) is required to use drugs extra label.

If ewes are well-nourished, the need for deworming should be minimal. If lambs are pastured, they will need to be closely monitored for signs of internal parasitism and treated accordingly with effective drugs. The current recommendation is to use combination treatments (more than one dewormer at a time) to treat clinically-parasitized animals. Numerous management practices can lessen the need for deworming.

Lamb management

As with cow and goat dairies, lambs are usually separated from their dams soon after birth, usually within 24 to 48 hours. Lambs may be allowed to consume colostrum from their dam before being separated for artificial rearing or they can be tube-fed colostrum. Since the ewe’s milk production peaks 3 to 5 weeks after parturition, early separation will result in significantly more milk being produced than if lambs are left with the ewes for any significant amount of time.An alternative to early separation is to leave the lambs on the ewes for the first 30 (sometimes 60) days, before initiating milking. This management scheme will reduce the labor associated with lamb rearing and will get the lambs off to a better start. At the same time, it will substantially decrease the amount of milk that can be marketed or used for cheese making. It is estimated that the lambs will consume nearly 25 percent of the ewe's total milk production. The risk of mastitis will also be greater if the lambs are allowed to nurse.

Another option is to let the ewes nurse their lambs for 30 days, but one week after lambing, begin separating the lambs from the ewes (at night) so that the ewes can be milked once per day (in the morning), after which time the ewes are returned to their lambs for the day. This "mixed" system improves lamb growth, but has been shown to lower the fat content of the milk collected during this period.

Rearing the lambs

In most sheep dairies, an automatic milk feeder is used to mix milk and dispense milk replacer to lambs. Lambs learn very quickly to nurse from an automatic feeder. Lambs should be fed a milk replacer that has been formulated for specifically for lambs, as ewe milk contains more fat and less lactose than cow and goat milk. Cow's milk may be a viable alternative for feeding lambs, if fat is added. In fact, the use of cow "waste" milk could significantly reduce the cost of rearing lambs artificially. Store bought cow's milk (with added fat) may be another low cost alternative, as it may have a lower cost than milk replacer.Dairy lambs are usually weaned by the time they are 30 days of age. For early weaning to be successful, lambs need to be eating dry feed as soon as possible. Lambs will begin to nibble on hay and grain at very young ages, but won't consume significant amounts of feed until they are approximately three weeks of age. The small amounts that lambs consume at the beginning are important to rumen function and the habit of eating.

Dry feed should be available to lambs as soon as they are moved out of lambing jugs into mixing pens. Young lambs need feeds that are palatable and ferment rapidly. Creep rations are usually based on corn and soybean meal. Soybean meal is the most palatable feed for lambs, while corn ferments well. At a young age, lambs prefer ground rations or ones made of crumbles. Pellets, whole grains, and oats are not very desirable for young lambs. But once lambs get older and have a fully functioning rumen, they can be fed these feeds. In fact, whole grain diets are less likely to cause digestive upsets. Hay is often not fed to artificially-reared lambs until after weaning, as it can predispose them to bloat.

If the ewes will be allowed to nurse their lambs, a creep area will need to be set up. Obviously, the area needs to be accessible to the lambs and inaccessible to the ewes. There should be plenty of openings in creep panels and good visibility so that ewes and lambs can see each other. The pen should be located in a common traffic area. The pen should be clean, dry, well-bedded, and well-lit.

Early weaning requires a high degree of management. It may be advisable for new dairy sheep producers to start with a less intensive lamb management system, as ewe management also requires a high degree of management.

Milking

Ewes can be milked by hand or by machine. Hand milking is usually only practical for milking a small number of ewes, though it is common in countries where large flocks are managed under very extensive conditions. Regardless of the method use, hygiene is of primary importance.

Ewes are usually milked on an elevated platform from the rear. A bucket system is portable and suitable for smaller dairies. Larger dairies can usually justify the expense of a "pit" parlor milking system. There are several different designs for parlor milking systems. Parlors usually have a single row of stanchions, parallel stanchions, or are rotary-style.

A separate milk room is required. A bulk tank is needed to cool the milk and store it until it can be sold or frozen. Milk can be carried in buckets to the milk room or a pipeline can be installed to move milk from the sheep to the milk room. If the milk will be frozen, additional equipment will be needed, as well as a freezer to store the frozen milk. Home-type freezers will not work because they cannot freeze the milk fast enough.

Twice a day milking is most common in commercial sheep dairies, but less frequent milking, especially during mid and late-lactation may be more economical. Less milk will be obtained when ewes are milked less frequently, but labor savings may more than compensate for the lower yield. Research is underway in several countries comparing different milking frequencies.

Nutrition

During lactation, dairy ewes have higher nutritional requirements than ewes raised for meat and/or wool. Inadequate feeding may reduce both daily milk production and the length of the lactation period. Nutrient requirements for parlor-milked ewes were published by the National Research Council (NRC) in 2007.

The table below contrasts the daily nutrient requirements of a 176-lb. ewe nursing twin lambs with a dairy ewe being parlor milked. The milk yield (lbs. per day) and nutrient requirements of the parlor-milked ewe are significantly higher than for the same size non-dairy ewe nursing twin lambs.

Source: Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants (2007) As with all sheep, dairy ewes can be fed a variety of feedstuffs to meet their nutritional requirements. Good quality forage is essential to the dairy ewe, but forage alone will not meet the nutritional requirements of high-producing dairy ewes. Grain is usually fed when the ewes are in the milking parlor.

Some feeds (e.g. fish meal) can impart undesirable flavors to the milk and should not be fed in large quantities during lactation. An unlimited water supply is also important to the lactating ewe. It takes lots of water to make a lot of milk, as milk is 88 percent water! The water should be clean, fresh, never frozen, and always available.

Marketing

In order to sell milk or milk products (for human consumption), a farm must be licensed and meet various requirements pertaining to milk quality and safety. Facilities must pass local or state inspections. For the most part, the regulations are the same as for cow and goat dairies.

As far as regulations go, there may be differences between states (and countries). Raw milk and cheese sales are permissible in some states and under certain conditions. People interested in commercial sheep dairying need to contact their state milk inspector before they make any significant investment. For each producer, there will be a certain size enterprise (number of ewes) that justifies the expense necessary to meet inspection and licensing requirements.

Selling fluid milk to a commercial cheese-maker is the most straight forward way to market sheep milk, but this option may not be available to many producers. Freezing the milk may facilitate fluid milk sales. In many situations, the dairy sheep farmer must be producer, cheese-maker, and marketer.

On-farm cheese-making is becoming popular, especially in areas that lack commercial buyers for sheep milk or as a means of adding value to farm production. To make cheese, separate cheese-making facilities are required. Farmstead cheeses can be sold at various outlets, including farm stores, farmers markets, retail outlets, and internet sales.

Dairy Sheep Basics

<== SHEEP 201 Index

Copyright© 2021. Sheep 101 and 201.