- Sheep 201 Index

- Other web sites

Healthy lamb

Bluetongue

Image source: Wyoming State Vet Lab

Bottle jaw

Healthy eye color

Club lamb fungus

Dystocia

Epididymitis

Image source:

Colorado State University Extension

Flystrike

Image source: Wool is Best

Foot rot or scald

Infectious keratoconjunctivitis

Hairy Shaker disease

Image source: TeAra.govt.nz

Injured eye

Intraperitoneal injection

Johne's disease

Image link: TeAra.govt.nz

Parasitized lamb

Pizzle rot

Image source: Dept. of Ag Western

Cape

Polioencephalomalacia

Pulpy kidney disease

Image source: TeAra.govt.nz

Scrapie

Scrotal hernia (congenital)

Scrotal hernia (acquired)

Scabies

Image source: Cornell University

"Sloppy mouth" - cause unknown

Soremouth

Swollen head

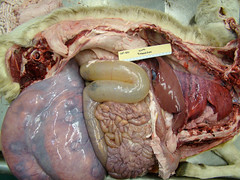

Enough tapeworms to cause

intestinal blockage and death

Tetanus

Image source: NADIS

Thin ewe

Uterine prolapse

White eye

White muscle disease

Image source: North

Carolina State University

Listing of sheep diseases, A-ZThis chapter is meant to provide an overview of the diseases that can affect sheep and lambs. For more information, including more detailed treatment options, you need to consult an animal health reference or seek advice from a qualified veterinarian or other animal health professional.

Sheep can be affected by a variety of infectious and noninfectious diseases. Some diseases that affect sheep are contagious to people. These are called zoonotic diseases or zoonosis. Some diseases, such as scrapie, must be reported to government authorities. Reportable diseases vary by state and country. Certain diseases prevent the import and export of livestock or have requirements for entry.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y ZAbomasal bloat

Abomasal bloat is mostly a disease of artificially-reared lambs, especially those that are hand-fed warm milk. It seldom affects lambs that are self-fed cold milk. Abomasal bloat is believed to be caused by a build-up of bacteria in the stomach of the lamb. Clostridial bacteria and species of Sarcina have been implicated in the US. Affected lambs have swollen bellies and abdominal discomfort. Treatment (sodium bicarbonate) is not always rewarding. The addition of yogurt or probiotics to milk replacer has been shown to reduce the incidence of abomasal bloat. It is especially important to vaccineate artificially-reared lambs for the enterotoxemias.Read article on abomasal bloat=>

Abomasal emptying defect (AED)

Abomasal emptying defect is a disease that primarily affects Suffolk sheep and is characterized by distension and impaction of the abomasum. Symptoms include anorexia and progressive weight loss. There is no known cause or curative treatment. The disease occurs sporadically and is considered rare.

Abortion

Abortion is when a ewe's pregnancy is terminated, and she loses her lambs, or she gives birth to weak or deformed lambs that die shortly after birth. There are many causes of abortion in sheep, both infectious and non-infectious. In the US, the most common infecious causes of abortion in sheep are Chlamydia (Enzootic abortion), Campylobacter (Vibrio), and Toxoplasma gondii (Toxoplasmosis). It is important to note that these organisms may also cause abortion (miscarriage) in women. As a precaution, pregnant women should not handle fetuses or placental fluids.

Read Infectious Causes of Abortion in Ewes =>Brucellosis

Brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by bacterium of the genus Brucella. Various Brucella species affect sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, dogs, and other animals. In infected ruminants, brucellosis commonly causes abortion during the second half of gestation. Sheep are less susceptible than cattle, and brucellosis is not considered a common cause of abortion in sheep. Ovine brucellosis mainly affects rams, causing lesions in their reproductive organs (called epididymitis).

Cache Valley Virus

Cache Valley Virus is a bunyavirus that occasionally causes abortion storms in sheep. The virus is spread by mosquitoes to pregnant ewes. If a ewe is infected at less than 28 days of gestation, the embryos usually die and are reabsorbed. If a ewe is infected after 45 days of pregnancy, there are usually no adverse effects.

If infection occurs between 28 and 45 days of gestation, the fetuses usually develop the "A-H syndrome," resulting in various congenital abnormalities (birth defects) affecting the central nervous system. Ewes that are infected usually show no signs of disease and develop good immunity that lasts for several years. Cache Valley virus is similar to Akabane Disease except that it only affects sheep.Campylobacteriosis (Vibrio, vibriosis)

Campylobacterisis is a common cause of abortion in ewes. Abortion during the last month of pregnancy, stillborn lambs, and the birth of weak lambs are common signs of vibrio abortion. The organisms which cause abortion are Campylobacter jejuni or Campylobacter fetus. Ewes are infected by oral ingestion. The incubation period from the time of infection and abortion is only two weeks.Vaccination can be effective in the face of an outbreak. Feeding of antibiotics has also been shown to be effective at reducing abortions caused by vibrio. Disease spread can be prevented by isolating the aborting ewe, disposal of the fetuses and membranes, and disinfecting the affected area. Infected ewes usually recover after aborting and are immune to re-infection. A vaccine is available. It should be administered prior to breeding and repeated in 60 to 90 days, then annually.

Chlamydia (enzootic abortion, EAE)

In the U.S., Chlamydia is the most common cause of abortion in ewes. It is transmitted from aborting sheep to other susceptible females. Ewe lambs are usually the most susceptible on farms where the organism is present. The bacteria which causes enzootic abortions in ewes is called Chlamydia psittici. Chylamydia causes abortion during the last month of pregnancy and may also result in the birth of lambs that die shortly after birth.

The organism may also cause pneumonia in young lambs, but the chlamydia species that causes abortion is not associated with conjunctivitis or arthritis. Chlamydia abortions can usually be stopped or reduced by treating the entire flock with tetracycline. A vaccine is available. It should be administered 60 days prior to breeding and repeated in 30 days, then annually just prior to breeding.Leptospirosis

Sheep are generally more resistant to leptospirosis than cattle, swine, and most other domestic animals. Abortion due to this disease may occur during the last month of pregnancy. A blood test of aborting sheep will confirm diagnosis. The problem can be prevented with annual vaccination with a 5-strain leptospirosis vaccine.Q Fever

Q Fever is a disease caused by the bacteria Coxiella burnetti. The disease is found worldwide except for New Zealand. Sheep, goats, and cattle are most likely to get Q fever. The most common sign of Q fever is abortion during late pregnancy. However, most animals do not show any signs. Animals get Q fever through contact with body fluids or secretions. Q fever is zoonotic (transmissible to people). It causes influenza-like symptoms.Rift Valley Fever (infectious enzootic hepatitis)

Rift valley disease is a viral disease of sub-Saharan Africa. The virus attacks the liver and causes symptoms ranging from fevers and listlessness to hemorrhage and abortion rates approaching 100%. It is transmitted by mosquitoes. There is no specific therapy for infected animals.

Vaccination of animals against RVF has been used to prevent disease in endemic areas and to control epizootics. Rift Valley fever has not occurred in the United States. However, there has been concern that it could become permanently established in the U.S. if it does enter the country. Rift Valley fever is more deadly than West Nile virus.Salmonella

In the US, salmonella abortion is a less common cause of abortion in sheep, but probably occurs more often than recognized. The two major factors determining whether a pregnant ewe will abort from Salmonella are stress on the ewe and the number of Salmonella bacteria the ewe ingests.

Abortions may occur earlier in gestation but are most common in the last month of gestation. Most of the ewes show diarrhea and some will die from metritis, peritonitis, and septicemia. Healthy lambs may also contract the disease and die.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is another common cause of abortion in ewes. It is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan parasite which causes coccidiosis in cats. Thus, cats are the carrier for the causative organism. Toxoplasma abortion in ewes follows ingestion of feed or water that has been contaminated with oocyte-laden cat feces. The organism migrates to the placenta and fetuses, causing their death and expulsion. Ewes will abort during the last month of pregnancy or give birth to dead or weak lambs that usually die from starvation.

Infection in the first two months of gestation results in embryonic death and re-absorption. There is some evidence that Rumensin® and Deccox® will partially prevent toxoplasmosis in pregnant ewes. Limiting cat populations (spay and neuter farm cats) and preventing contamination of sheep feed and water with cat feces will help to prevent disease outbreaks. There is no vaccine available in the U.S. for toxoplasmosis.

Acidosis

(lactic acidosis, ruminal acidosis, grain overload, grain poisoning)

Acidosis is a common metabolic disease. It is caused by excess consumption of grain or pellets to which animals are unaccustomed to. The feeds are rapidly fermented in the gut, resulting in large quantities of lactic acid being produced, which lowers the pH in the rumen.Affected sheep appear depressed and listless and may have abdominal pain. Acidosis can be a life-threatening condition. Affected sheep should be drenched with an antacid such as carmalax, bicarbonate of soda (baking soda), or products containing magnesium carbonate or magnesium hydroxide.

Acidosis can be prevented by proper feeding management. Concentrates (grain) should be introduced to the diet slowly and increased incrementally to give the rumen time to adjust. Whole grain feeding reduces the risk of acidosis, as does feeding grains that are higher in fiber, e.g. oats and barley.

Arthritis

Arthritis in sheep is an inflammation of the joints of the legs, resulting in loss of production, loss of carcass value, and deaths. The main cause of arthritis in sheep is when bacteria enter the body via broken skin. The common times when sheep will be susceptible to arthritis are: 1) at or soon after birth with infection through the umbilical cord; 2) during docking, castration, and ear tagging; 3) through shearing wounds; and 4) other wounds.

There are several bacteria that may be implicated in arthritis. The most common is Erysipelothix rhusiopathiae. Signs appear 2 to 14 days after infection. Affected joints become swollen, hot, and painful, resulting in the lamb becoming reluctant to move. For most types of arthritis, the only treatment is a course of massive doses of antibiotics. Prevention is the result of good sanitation and hygiene.

Bacterial meningitis

Bacterial meningitis occurs sporadically in lambs. It most commonly affects lambs 2 to 4 weeks old. The entry point of the bacteria is not clearly understood. Inadequate transfer of passive antibodies predisposes lambs to infection. Early clinical signs include depression, hunger, and failure to follow dams. Affected lambs may have abnormal gait. Their head is often held lower in a rigid extension. Response to treatment with antibiotics and corticosteroids is usually poor.

Bent leg (a form of rickets)

Bent leg is a form of rickets and is due to a malfunction of bone metabolism during growth. It occurs during the rapid growth phase of the lamb, usually between 6 and 12 months of age. It occurs primarily in rams but can occur in ewes. It is more common in Rambouillet and related breeds. Similar conditions occur in cattle, horses, dogs, poultry, and people.

It can be prevented by 1) feeding balanced rations; 2) avoiding the use of too much high energy or high protein feeds (rapid growth and nutritionally "pushing" animals for growth is a factor in all species for increased incidence of rickets); 3) providing a calcium to phosphorus ratio of at least 1.5 to 1; 4) supplementing the ration with 300 IU of vitamin D (per 100 lbs. of body weight per day); 5) providing adequate magnesium; 6) shearing young rams in early winter to allow more skin surface for vitamin D conversion; and 7) providing housing that provides good exposure to sun during the winter.

BloatBloat is a common metabolic disease of ruminants. It occurs when rumen gas production exceeds the rate of gas elimination. Gas then accumulates causing distention of the rumen. The skin on the left side of the animal behind the last rib may appear distended. Bloat can be a medical emergency, and timely intervention may be necessary to prevent death. Bloat is a common cause of sudden death in livestock. It usually results from nutritional causes.

There are two types of bloat: frothy and free gas.

Frothy Bloat (pasture bloat)

Frothy bloat is usually associated with the consumption of leguminous forages but may also occur in sheep grazing lush cereal grain pastures or wet grass pastures or consuming grain that is too finely ground. Animals with frothy bloat can be treated with anti-foaming agents such as cooking oil or mineral oil or a commercial product such as Poloxalene.Free Gas Bloat (feed lot bloat)

Free grass bloat is associated with grain feeding and occurs when animals were not given enough of an adjustment period. Many of the same factors causing acidosis are associated with free-gas bloat. Simple passage of a stomach tube may be effective at relieving free gas bloat. Inserting a trochar or needle (14 gauge) into the abdomen is a life-saving procedure that should only be attempted as a last resort.

Bluetongue

Bluetongue is an insect–transmitted, viral disease of sheep, cattle, goats, and other ruminants, such as white–tailed deer and pronghorn. It is particularly damaging in sheep; half the sheep in an infected flock may die. In cattle and goats, however, bluetongue viruses cause very mild, self–limiting infections with only minor clinical consequences. A bluetongue virus infection causes inflammation, swelling, and hemorrhage of the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and tongue.

Inflammation and soreness of the feet also are associated with bluetongue. In sheep, the tongue and mucous membranes of the mouth become swollen, hemorrhagic, and may look red or dirty blue in color, thus giving the disease its name. Bluetongue viruses are spread from animal to animal by biting gnats. In the United States, the disease is most prevalent in the southern and southwestern States.

Animals cannot directly contact the disease from other animals. The bluetongue vaccine for sheep is only effective against certain serotypes, will not prevent the disease, and may cause adverse reactions. Pregnant ewes should not be vaccinated.

Border Disease

(hair-shaker disease, fuzzy lamb syndrome, BD)

Border disease is often seen in the newborn lamb which has a hairy coat and trembles uncontrollably. It is caused by a virus and causes a wide variety of symptoms depending upon the stage of pregnancy when the ewe becomes affected. Sheep affected by border disease are characterized by open ewes, abortion, weak and frail lambs, abnormal hair coat, and nervous symptoms that cause the lamb to shake.

The most common clinical symptom is abortion of macerated or mummified lambs. Border disease is usually brought into a flock by new additions that are carriers or when sheep are mixed with cattle that are shedding the Bovine viral disease virus. Bovine viral diarrhea vaccines for cattle cannot be recommended for use in sheep because border disease viruses most commonly isolated from sheep are antigenically distinct from bovine viral diarrhea viruses most common in cattle. There is no treatment and the disease will not respond to antibiotics.

Caseous Lymphadenitis

(CLA, CL, boils, abscesses, cheesy gland)

Caseous lymphadenitis is an infectious, contagious disease that primarily affects the lymphatic system, though other organs can be affected. It is caused by the bacteria Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Infection results in abscess formation in the lymph nodes which when cut or ruptured, discharge pus containing the bacteria into the immediate surroundings. When the nodes spread internally, affected ewes slowly lose weight and eventually become emaciated.

CL is the third leading cause of carcass condemnation in the US. The disease is controlled by culling visible infected animals and practicing good hygiene at shearing time. There is a vaccine licensed for sheep. It has been shown to both decrease the number of abscesses in sheep and the number of sheep that develop abscesses.

Clostridial Diseases

Clostridial organisms of various types are found in the soil, where they can survive for a very long time. Most clostridial organisms also occur quite naturally in the gut of healthy animals. Sheep can be infected with various clostridial diseases – black leg, botulism, malignant edema, red water disease, enterotoxemias (several types), and tetanus. The most common are enterotoxemia types C & D and tetanus.Enterotoxemia type C

(hemorrhagic enteritis, bloody scours)

Enterotoxemia type C is caused by Clostridium perfringins type C and affects lambs during their first few weeks of life, causing a bloody infection of the small intestine. It is often related to indigestion and predisposed by a sudden change in feed such as beginning creep feeding or sudden increase in milk supply. Treatment (antitoxin injected under the skin) is usually unrewarding. Vaccination of pregnant ewes 30 days before lambing is recommended as prevention. The antitoxin can be given to provide immediate short-term protection.

Enterotoxemia type D

("classic" overeating disease, pulpy kidney disease)

Overeating disease is one of the most common sheep diseases in the world. It is caused by Clostridium perfringins type D and most commonly strikes the largest, fastest growing lambs in the flock. It is caused by a sudden change in feed that causes the organism, which is already present in the lamb's gut, to proliferate causing a toxic reaction.

It is most commonly observed in lambs that are consuming high concentrate rations but it can also occur when lambs are nursing heavy milking dams. It usually affects lambs over one month of age. It is characterized by sudden deaths, but can also be chronic in nature. Treatment (antitoxin injected under the skin) is usually unrewarding. Vaccination of pregnant ewes 30 days before lambing is recommended as prevention. Lambs should be vaccinated twice at approximately 6 to 8 and 10 to 12 weeks of age. Pasture-fed lambs that are brought in for feeding should be vaccinated.Tetanus (lock jaw)

Tetanus is caused by Clostridium tetani, a soil inhabitant that is a prolific spore producer. This disease is usually related to docking and castrating by elastrator bands, though any wound can harbor the tetanus organism.

Signs of tetanus occur from about four days to three weeks or longer after infection is established in a wound. The animal may have a stiff gait, "lockjaw" can develop, and the third eyelid may protrude across the eye. The animal will usually go down with all four legs held out straight and stiff and the head drawn back. Convulsions may occur.

Treatment consists of the tetanus anti-serum and antibiotics. It is usually unrewarding. Tetanus can be prevented by vaccinating pregnant ewes 30 days before lambing. If pregnant ewes were not vaccinated for tetanus, the tetanus anti-toxin can be administered to lambs at the time of docking and/or castrating. The tetanus anti-toxin provides immediate short-term immunity and can be used during high risk periods to prevent disease outbreaks.Less common Clostridial Diseases

Enterotoxemia type B (lamb dysentery)

Clostridium perfringins type B causes lamb dysentery. It usually affects strong lambs under the age of 2 weeks. Symptoms include sudden death, listlessness, recumbency, abdominal pain, and a fetid diarrhea that may be blood-tinged. On post-mortem, intestines show severe inflammation, ulcers, and necrosis. The mortality rate approaches 100 percent. Cl. perfringins type B is not common in the U.S., but is frequently found in England, Europe, South Africa, and the Near East.Black Disease

Black disease occurs in sheep in areas where liver flukes are known to occur. Infections are caused by the bacterium Clostridium novyi, which becomes active in the liver tissue damaged by the liver fluke. Control relies on vaccination and elimination of liver flukes.Blackleg

Blackleg is disease of cattle and less frequently of sheep. It is caused by the soil-borne bacteria Clostridial chauvei. The disease develops rapidly in affected animals and often deaths occur before the owner has noticed any sickness. Vaccination is the only means of protection against blackleg.Malignant Edema

Malignant edema is caused by the bacterium Clostridium septicum. In sheep, blackleg and malignant edema are indistinguishable. The disease is not common in sheep in North America. In areas where the disease is known to occur, lambs can be vaccinated.

Cobalt deficiency (vitamin B12 deficiency)

The only known animal requirement for cobalt is as a constituent of Vitamin B12, which has 4% cobalt in its chemical structure. This means that a cobalt deficiency is really a vitamin B12 deficiency. Microorganisms in the rumen are able to synthesize vitamin B12 needs of ruminants if the diet is adequate in cobalt. Ruminants must consume cobalt frequently in the diet for adequate B12 synthesis.

Cobalt deficiency causes lack of appetite, lack of thrift, severe emaciation, weakness, anemia, decreased fertility, and decreased milk and wool production. Weeping eyes, leading to a matting of wool on the face, is another common symptom. Sheep are more susceptible to cobalt deficiency than cattle. Cobalt deficiency also impairs the immune function of sheep which may increase their vulnerability to infection with worms.

The diagnosis of cobalt deficiency is usually based on blood (serum) vitamin B12 concentrations, which reflect immediate cobalt intake. Short-term supplementation of sheep with cobalt is usually achieved through oral drenching with cobalt sulfate or vitamin B12 injections.

Congenital defects are abnormalities of structure or function present at birth. They may be caused by genetic or environmental factors or combinations of both. The causes of many defects remain unknown. Developmental defects may be lethal, semi-lethal, or have little effect on the health and performance of the animal. If the cause is genetic, inbreeding will increase the frequency of deleterious genes.

Copper deficiency

In sheep, copper deficiency is not diagnosed nearly as frequently as copper toxicity, but it may occur in regions where soils and forages are low in copper or have elevated levels of molybdenum. Some feedstuffs may also contain mineral levels that are antagonistic to copper absorption. In adult sheep, signs of copper deficiency are usually sub-clinical and hard to identify. Severe deficiencies may result in "steely" or "stringy" wool that lacks crimp and tensile strength.

Young animals are more susceptible to copper deficiency, as milk is a poor source of copper. Affected lambs may show signs of "swayback" or have difficulty standing or walking (known as ataxia). Oral administration of copper sulfate or other chelated forms of copper is the usual treatment for copper deficiency.

Copper toxicity

Sheep are ten times more susceptible to copper toxicity than cattle. When consumed over a long period of time, excess copper is stored in the liver. No damage occurs until a toxic level is reached at which time there is a hemolytic crisis with destruction of red blood cells. Most outbreaks of copper poisoning in sheep can be traced to feeding supplements containing copper levels that have been formulated for cattle or swine.

Copper is closely related to molybdenum, and copper toxicity occurs when the dietary ratio of copper to molybdenum increases about 6-10: 1. Affected animals suddenly go off feed and become weak. An examination of their mucous membranes and white skin will reveal a yellowish-brown color. Their urine will be a red-brown color due to hemoglobin in the urine.

Treatment of copper toxicity involves the use of ammonium molybdate and sulfate compounds.

Read Copper Toxicity in Sheep =>

Diarrhea (Scours)

Diarrhea is defined as an increased frequency, fluidity, or volume of fecal excretion. There are many causes of diarrhea: bacterial, viral, parasites, diet, and stress. It is not possible to definitively determine the infectious organism by looking at the color, consistency, or odor of the feces. A definitive identification requires a sample for microbiological analysis. Diarrhea is a complex, multi-factorial disease involving the animal, the environment, nutrition, and infectious agents.

Diarrhea should not be considered an illness in and of itself but rather a symptom of other more serious health problems in sheep and lambs. Diarrhea is not always the result of an infectious disease. It can be induced by stress, poor management, and nutrition. Before treating an animal for diarrhea, it is essential to determine why the animal is scouring. Many of the common causes of diarrhea are self-limiting, and the major goals of treatment are to keep the animal physiologically intact while the diarrhea runs its course.In some animals, rehydration and other supportive care may be necessary. Over-the-counter medications such as Pepto Bismal (Bismuth subsalicylate) and Kaopactate (Kaolin pectin) can be used to treat non-infectious causes of diarrhea. Probiotics or yogurt are always a good treatment option for scouring animals.

Read Diarrhea (scours) in small ruminants =>

Dystocia (lambing difficulty)

Most ewes deliver their lambs without assistance; however, there are instances when producers must be prepared to assist with difficult deliveries. Difficult births can be caused by 1) abnormal presentation of the lamb(s); 2) an unusually large lamb; 3) a fat ewe; 4) a small pelvic area; and 5) disease.

The normal delivery position for a lamb is the head and two front feet being delivered first. If lambs cannot be delivered after a reasonable amount of time and effort, competent assistance should be sought. A caesarean section is sometimes necessary to deliver lambs that cannot be delivered normally.

E. Coli scours (watery mouth)

E. coli scours is an opportunistic disease that is usually associated with sloppy environmental conditions and poor sanitation. It generally occurs as a diarrhea problem in two to four-day-old lambs. Affected lambs salivate and have a cold mouth; thus, the common name, "watery mouth." Dehydration, coma, and death usually occur within 12-24 hours following the onset of clinical signs of scours.

Treatment of E. coli scours usually involves rehydrating the lamb with oral, subcutaneous, or intraperitoneal fluids and treatment with appropriate antibiotics. Prevention of E. coli scours in lambs should really be the key focus for any flock. Lambing barn sanitation and creating a clean, dry environment for newborn lambs are the key factors related to preventing outbreaks of E. coli scours.

Entropion (inverted eye lid)

Entropion is a heritable trait in which the lower eyelid is inverted, causing the eyelashes of the lower lid to brush against the eye. Entropion should not be left untreated. The constant irritation results in tearing and can lead to corneal ulceration, scarring, and blindness. It may affect one or both eyes.

Mild cases of entropion can be treated by injecting a long acting antibiotic under the skin of the affected eyelid. Sometimes, staples, sutures, or clips will need to be applied to the skin surface of the affected eyelid. Rams carrying this trait should not be used for breeding.

Epididymitis (Brucella Ovis)

Epididymitis is a venereal disease of rams caused by the bacteria Brucella ovis. Epididymitis means inflammation of the epididymitis, the tubular portion of the testicle that collects the sperm produced by the testes and stores it until it is ready to transport. Severely affected rams will often have at least one enlarged epididymis and may show pain when the testicle is manipulated.

Epididymitis causes varying degrees of damage. It may cause infertility by affecting the ram's ability to produce viable sperm. It is the number one ram fertility problem seen in the sheep industry. Epididymitis is contagious and is transmitted during homosexual activity or during the breeding season via the ewe. Only about half of the rams affected by epididymitis respond to antibiotic treatment. Damage is usually permanent. Prevention is to buy virgin or disease-free rams, to subject rams to diagnostic testing, and to cull affected rams.

External Parasites (ectoparasites)

External parasites that affect sheep include keds, ticks, lice, mites, and flies. Mange (sheep scab) in sheep is rare and a reportable disease in the U.S.Fly Strike

(blowflies, wool maggots, fleece worms, myiasis)

Fly strike is the infestation of the flesh of living sheep by blowfly maggots. Of all domestic animals, sheep are most often affected because of their wool, as particularly dirty wool attracts blowflies. Blowfly populations are greatest during the summer months.

Docking, shearing, and removal of dags (wool contaminated with feces) will help to prevent flystrike. Insecticides are another control measure. Hair sheep are less susceptible to fly strike due to their absence of wool. Blowflies are also attracted to wounds, foot rot, weeping eyes, or sweat around the base of the horns of rams.

Sheep Keds (or ticks)

Sheep keds are wingless, reddish brown biting flies that resemble, and are sometimes called, ticks. They use piercing- sucking mouthparts to feed on blood. High ked populations cause unthriftiness and emaciation and make animals more susceptible to diseases and other stresses. Sheep keds are readily controlled with insecticides. Treatment is recommended immediately after shearing. Keds can only survive off the animal for about a week. Keds do not thrive well on the short hair of hair sheep.Lice

Lice are quite small, ranging from 1/20-inch to 1/10-inch long. They spend most of their time next to the skin and are difficult to see within dense wool or hair. Three species of lice are found on sheep. The primary animal reaction to lice is itching. Severe infestations can cause anemia. Various insecticides can be used to control lice on sheep.Nasal bots (bot flies, head bots)

The sheep bot fly is a fuzzy, yellowish-gray, or brown fly that deposits tiny larvae on the muzzles or nostrils of sheep. The larvae migrate into the nostrils and head sinuses and develop. A snotty nose is the most common symptom. Animals will hold their heads down or in a corner to escape the flies. Weight reductions of up to 4 percent have been attributed to bot infestations in some studies. The highest bot levels are seen in November and December. A systemic insecticide formulation containing ivermectin is effective against larval stages of the nasal bot.Scabies

(sheep scab, psoroptic mange, wet mange)

Sheep scab is a very contagious disease, caused by mites feeding on the surface layers of the sheep's skin. Severe itching occurs, wool or hair falls out in patches, and the skin becomes reddened, crusted with scabs and sore. Positive diagnosis can be made only by scraping lesions and examining the scrapings microscopically for mites. The preferred method of treatment is dipping with insecticides. Scabies has been eradicated from the United States.

Facial eczema

Facial eczema is a condition of severe dermatitis in cattle, sheep, and goats caused by a toxin in spores of the saprophytic fungus Pithomyces chartarum, which lives in dead vegetative material in pastures, especially perennial ryegrass. Facial eczema is an example of "secondary photosensitization," in which the skin lesions are really the secondary result of liver damage, rather than the direct result of a plant toxin. The liver damage in facial eczema is caused by the toxin sporidesmin in the fungus spores.

Facial eczema is relatively common in areas of New Zealand and has also been observed in Australia, South Africa, and in irrigated perennial ryegrass fields in the United States (Oregon). Perennial ryegrass is the grass species most associated with facial eczema. P. chartarum as does not grow well in legumes. The occurrence of facial eczema is also influenced by livestock genetics.

Performance testing programs in New Zealand have identified genetic lines of sheep that can tolerate relatively high toxin situations. Animals suffering from facial eczema should be removed from the contaminated pasture and provided with shade, cool water, and a good diet. Feeding high levels of zinc may help prevent facial eczema.

Fescue Toxicosis

Most Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea) is infected with a fungal endophyte. The endophyte produces toxins that cause a number of problems for grazing animals, though sheep appear to be less affected than cattle and horses. However, sheep are prone to "fescue foot," hyperthermia, poor wool production, and reproductive problems, as well as lowered feed intake and the resulting poor weight gains. Diluting Kentucky 31 tall fescue with legumes and supplementing with other feeds will reduce the toxic effects of fescue on livestock. Alternative tall fescue cultivars are also available. Stockpiled fescue is less toxic.

Foot-and-mouth disease

(FMD, hoof-and-mouth disease)

Foot-and-mouth disease is a severe, highly communicable viral disease of cattle and swine. It also affects sheep and goats and other cloven-hoofed animals. The disease is characterized by fever and blister-like lesions followed by erosions on the tongue and lips, in the mouth, on the teats, and between the hooves.

While many affected animals recover, the disease results in a weakened state, loss of weight, and reduced production of milk and meat. Foot-and-mouth disease in adult sheep and goats is frequently mild or unapparent but can cause high mortality in young animals. Sheep and goats are sometimes the reservoir of infection. The disease is virtually never harmful to humans but is highly contagious among those animals which are vulnerable to this virus.

The United States has been free from foot-and-mouth disease since 1929.

Footrot

Footrot is one of the most economically devastating diseases in the sheep industry. It is caused by the interaction of two anaerobic bacteria: Bacteroides nodosus, which can only live in the animal's hoof; and Fusobacterium necrophorum, which is a normal inhabitant of soil and sheep manure.

Lameness in one or more feet is the most common symptom of footrot, though not all lame sheep have footrot. Footrot has a characteristic foul odor. Footrot can be controlled and/or eradicated by a combination of hoof trimming, vaccination, foot bathing and soaking and culling. Zinc sulfate is considered to be the most effective foot rot treatment. Footrot is highly contagious.

Foot Scald (benign footrot and ovine interdigital dermatitis)

Foot scald causes the tissues between the sheep's toes become blanched or white, or red and swelled. It is caused by a soil bacteria that is present in most environments and manifests itself during wet conditions. It is easier to treat than foot rot. Placing sheep in a dry area away from mud may clear the condition. Individual animals can be treated with Koppertox. Groups of animals may be treated with a zinc sulfate foot bath.

Goiter

Goiter is an enlargement or swelling of the thyroid gland. Affected lambs have a swollen throat. They are often born with little or no wool. They are weak and often die of starvation. Treatment is usually unrewarding. But if the condition is not advanced, the lamb may survive.

Goiter in newborn lambs is due to a deficiency of iodine in the pregnant ewe's diet. It can be prevented by providing iodized salt in the diet of gestating ewes. The salt mixture should contain 0.007 percent of available iodine. An iodine deficiency may also result in reduced yield of wool and reduced conception rate in the flock.Well-fed hair sheep lambs often display a throat swelling that resembles goiter. It is not. It is often called "milk goiter."

Grass tetany (grass staggers, magnesium deficiency)

Grass tetany is a complex disease traditionally associated with a magnesium deficiency. All ruminants are susceptible. Magnesium deficiency in sheep most commonly occurs in an acute form during the last 4 to 6 weeks of pregnancy. Affected ewes exhibit sensitivity to touch and trembling of the facial muscles; some are unable to move, others move stiffly; extreme cases collapse and show repeated tetanic spasms with all four limbs rigidly extended.

Low blood magnesium can be caused by low levels of magnesium in lush spring grass or by mineral imbalances such as high potassium and nitrogen or low calcium in the diet. Ewes with grass staggers are often low in calcium as well as magnesium. It is therefore wise to use a combined treatment of calcium borogluconate and magnesium hypophosphite. Producers can add about 10 to 20 grams of commercial or homemade supplemental magnesium to livestock diets to prevent grass tetany. Magnesium oxide is one of the best and cheapest magnesium sources.

Hypothermia (chilling)

Hypothermia is a leading cause of death in neonatal lambs. Mild to moderate hypothermia is characterized by a body temperature between 98° and 102°F. Severe hypothermia occurs when body temperature is below 98°F. Hypothermia is caused by excess body heat loss combined with reduced heat production. Newborn lambs are unable to regulate their body temperature during their first 36 hours.Severely hypothermic lambs need to be removed from the ewe for treatment. If they are less than five hours old, they should receive an intraperitoneal injection of a warm 20 percent dextrose (glucose) solution. Wet lambs should be towel dried and supplemented with heat or put in a warming box using dry heat (heat lamp or hair drier). Colostrum should be tube fed at a rate of 20 to 25 ml per pound of body weight. Once rectal temperature is normal, lambs may be returned to their dams.

Losses due to hypothermia can be prevented by providing ewes with adequate shelter for lambing, shearing ewes prior to lambing, confining ewes and lambs for one or two days to promote bonding, checking ewes for adequate milk production, and helping lambs suckle to ensure adequate colostrum intake. Coats or covers can help to prevent heat loss, but they should be removed once the lamb is capable of regulating its own temperature.

Internal Parasites

There are three broad types of internal parasite that can cause significant health issues in sheep: worms, flukes, and protozoa.Cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidium sp.)

Cryptosporidium species are tiny protozoan parasites closely related to coccidia. One major species, Cryptosporidium parvum, infects both farm animals and humans. C. parvum has a rapid, direct life cycle and infection occurs when viable oocysts in the environment are ingested by susceptible hosts, usually lambs under a month old.

Lambs as young as 3 days can be affected. Lambs are depressed and reluctant to suck while the diarrhea lasts. Very young lambs soon become dehydrated and die. In poor weather conditions, lambs may die of hypothermia. The illness may last for up to 10 days, and relapses after apparent recovery are common.

Coccidiosis (Eimeria sp.)

Coccidia are single-cell protozoa that are naturally in the sheep's digestive system. Young lambs are particularly susceptible to coccidia especially during periods of stress (e.g. weaning). Coccidia damage the lining of the small intestine, affecting absorption of nutrients. The most common symptom of coccidiosis is diarrhea. The diarrhea may be bloody or smeared with mucous.

The diagnosis of coccidiosis cannot be confirmed by identification of oocysts in fecal samples. Coccidiosis is mostly a management-related disease, caused by overstocking and poor hygiene. Coccidiosis can be prevented by including Lasolocid (Bovatec®), Monensin (Rumensin®), or Decoquinate (Deccox®) in the feed or mineral. Coccidiosis should be treated with Amprolium or sulfa medications.

Stomach worms

(Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, and Ostertagia sp.)

The internal parasites of greatest concern in sheep are usually the stomach worms, with the barber pole worm (Haemonchus Contortus) being of primary concern and the small brown stomach worm being of secondary concern. The barber pole worm is a blood-sucking parasite that pierces the mucosa of the abomasum, causing blood and protein loss.

The primary symptom of barber pole infection is anemia (blood loss). Anemia can be observed in the sheep by examining its lower eyelid, which will become paler (whiter) with increasing infestation. An accumulation of fluid under the jaw, called "bottle jaw" is also a tell-tale of barber pole infection.

The small brown stomach worm also burrows into the lining of the abomasum, but it causes typical digestive symptoms, especially diarrhea. Microscopically, it is difficult to differentiate between the barber pole worm and the brown stomach worm. The eggs only differ in size not appearance.Nematodirus spp.

The life cycle and transmission of Nematodirus differs from that of other sheep worms. Infective N. battus larvae generally don't survive for long on pasture when weather conditions are warm and dry but can survive for several months during cool and damp weather. The symptoms of nematodirus are scours, weight loss, and sudden death.

Tapeworms (Moniezia sp.)

There is disagreement as to whether tapeworms cause serious problems in sheep. They are generally considered to be non-pathogenic, though they can cause weight loss, diarrhea, and ill-thrift. A heavy infestation may cause an intestinal blockage and result in death. Heavy infestations may also predispose lambs to enterotoxemia.Tapeworms infect mostly suckling lambs. The only anthelmintics that are effective against tapeworms are the benzimadazoles (fenbendazole and albendazole) and Praziquantel (available extra-label in Quest® Plus or Zimectrin® Gold). Most research shows no benefit to treating lambs for tapeworms. Tapeworms are the only parasite that is visible in the feces and for this reason, they tend to cause concern among producers.

Read Tapeworms: Problem or Not? =>Lungworms

Lungworm larvae are passed in the feces, but travel to the respiratory system once they enter the sheep system. The symptoms of lung worm infection are not obvious unless the problem is severe. Lungworm infestations are most commonly diagnosed at necropsy or slaughter. The same anthelmintics that are effective against stomach worms are also effective against lung worms.Liver flukes (Fasciola hepatica)

Liver flukes can be problematic in wet areas. They are spread by snails and slugs. As the name would suggest, liver flukes damage the liver of the host animal. They cause blood loss, diarrhea, weight loss, and death. The only drugs that are effective against liver flukes (the adult form) are clorsulon (contained in Ivomec® Plus) and albendazole (Valbazan®).Meningeal worm

(Paralaphostrongylus tenius, deer worm, brain worm)

The meningeal worm is a parasite of the White Tail deer. Sheep, goats, llamas, alpacas, horses, and other animals are abnormal hosts for the parasite. After the host ingests the larvae, the larvae travel to the spinal cord causing gait abnormalities and other neurological symptoms and eventually paralysis and death. When the parasite reaches the sheep's brain, it will kill them.

Meningeal worm infection cannot be detected in the live animal, except from spinal fluid. When meningeal worm is suspected, high doses of anthelmintics and anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended. Fenbendazole (SafeGuard®) is the anthelmintic of choice, as it can cross the blood-brain barrier. Cornell University has recently validated treatment protocols. Infections can be prevented by limiting exposure to deer or by controlling snail populations, since the parasite requires snails to complete its life cycle.

Read Meningeal Worm =>

Johne's Disease (paratuberculosis)

Johne's Disease (pronounced "Yo nees") is a disease that affects the intestines of mostly ruminants. It is most commonly observed in dairy cows, but may also affect beef cattle, sheep, and goats. It is caused by a hardy bacteria called Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. The strain that affects sheep is different than the one that affects cows, though there is an intermediate strain that sheep are susceptible to.While cattle experience diarrhea, in sheep, Johne's tends to be more of a wasting disease. Control of the disease in infected flocks is difficult due to the lack of a reliable live animal test. No Johne's vaccine is available for sheep in the US. Colostrum from other sources (cows, goats) could be a source of infection in sheep flocks. The is no treatment for Johne's disease.

While Johne's disease has been linked to Crohn's disease in people, no causative association has been confirmed.

Download Johne's Disease Q & A for Sheep Owners =>

Joint or navel ill

Joint ill occurs in lambs up to one month of age. Affected lambs are often lame in several joints, usually limb joints, including fetlocks, knees, hocks, and stifles. Affected joints are hot and painful. The lambs are dull, feverish, and clearly unthrifty. Some may have swollen, infected navels, while others may have symptoms of pneumonia or meningitis.

The infection is usually caused by strains of streptococci, though coliforms and occasionally Actinomyces pyogenes may be isolated. Affected lambs should be treated with a long-acting penicillin. Joint ill is prevented by good hygiene and using a navel dip, such as betadine or gentle iodine.

Lameness

It has been estimated that 80 percent of the flocks in Great Britain have lame sheep. Lameness can be a sign of several foot conditions – some of which are very serious – as well as some other problems. These include foot rot and scald, strawberry foot, foot abscess, foot-and-mouth disease, bluetongue, ovine interdigital dermatitis (looks like scald), sore mouth, arthritis, nutritional deficiencies, mineral excesses, and physical injuries. The more common foot problems can be avoided or minimized if good husbandry practices are followed. Regular hoof inspection and foot paring will prevent many problems.

Laminitis (founder)

Lameness related to laminitis is caused by an inadequate flow of blood in the foot. Signs are heat in the feet. Laminitis is normally associated with digestive problems resulting from excessive intake of grain (grain overload/acidosis), which usually masks the effects on the feet. Such animals usually die before the feet become involved. Recovered animals may exhibit foot growth and/or permanent lameness. Feeding management is key to the prevention of laminitis/founder.

Listeriosis (circling disease)

Listeria monocytogenes, the bacteria that causes listeriosis, is widely distributed in nature and is found in soil, feedstuffs, and feces from healthy animals. Listeriosis is most commonly associated with the feeding of moldy silage or spoiled hay, but because the organism lives naturally in the environment, listeriosis may occur sporadically.

Listeriosis usually presents itself as encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) but may also cause abortion in ewes. Sheep with the neurological form of the disease become depressed and disoriented. They may walk in circles with a head tilt and facial paralysis. Mortality is high and treatment (high doses of antibiotics) is generally not effective.

Mastitis (hard bag, blue bag)

Mastitis is an inflammation (or infection) of the mammary gland (udder) which is usually caused by a bacterial infection. The bacteria that most commonly cause mastitis in ewes are Staphylococcus aureus and Pasteurella hemolytica. There are two types of mastitis: acute and chronic. The glands of ewes with acute mastitis may be discolored and dark, swollen and very warm. The affected ewe may be reluctant to walk, may hold up one rear foot, and may not permit her lambs to nurse. Ewes with chronic mastitis often go undetected.While no drugs are approved for sheep, mastitis is usually treated with intramammary infusions of antibiotics, systemic antibiotics, and anti-inflammatory drugs. There is no vaccine for mastitis. It is best prevented by good management and sanitation. Heavy milkers are more prone to mastitis. There is also a genetic component.

Read Mastitis in Ewes and Does =>

Measles

(sheep measles, cysticerosis)

Sheep measles (Cysticercus ovis) is the intermediate or larval stage of the cestode (tapeworm) Taenia ovis, the adult stage of which is found in the small intestine of dogs (sheep host the larvae stage). Sheep measle lesions are found in the heart, diaphragm and other muscles of sheep and goats. Although not considered to be a human health hazard, carcasses can be condemned on account of sheep measles.

There are no clinical signs of cysticerosis in sheep. Currently diagnosis is only made by finding the cysts at slaughter. To prevent sheep measles, dogs and other canines should not be allowed to feed on sheep or goat carcasses. Dogs should be dewormed for tapeworms. Any dog given access to the farm should be required to be dewormed.

Milk fever (hypocalcemia, parturient paresis)

Milk fever is a metabolic disease affecting mostly pregnant ewes near term when calcium requirements are the highest. It is most commonly caused by an inadequate intake of calcium, but can also be caused by a ewe's inability to mobilize calcium reserves prior to or after lambing. Milk fever presents similar symptoms as pregnancy toxemia but can be differentiated by the affected ewe's response to calcium therapy.

Ewes in the early stages of milk fever can be administered calcium gluconate subcutaneously. More seriously affected ewes will require intravenous calcium and other supportive therapies. Milk fever can be prevented by providing proper levels of calcium in ewe diets, especially during late gestation.

Read Milk Fever Strikes =>

Ovine progressive pneumonia (OPP, lunger disease. Maedi-Visna)

Ovine progressive pneumonia is a slow developing viral disease that is characterized by progressive weight loss, difficulty in breathing and development of lameness, paralysis, and hard bag. It is very closely related to caprine arthritis-encephalitis virus (CAE) and is caused by a retrovirus. The OPP virus closely resembles Maedi-Visna which is a similar slow or retrovirus found in other parts of the world.

OPP is transmitted laterally to other susceptible animals or to offspring through ingestion of infected milk and colostrum. Veterinary diagnostic laboratory assistance is required for diagnosis. There is no treatment, but OPP can be eliminated from the herd using annual blood testing and removal of positive animals and removal of the lambs from the ewes prior to suckling.

It is estimated that over 50% of the flocks in the U.S. are infected with OPP with the number of sheep infected within a positive flock anywhere between 1% to 70%. However, the vast majority of infected sheep will never show respiratory disease or a wasting syndrome.

Pink eye (infectious keratoconjunctivitis)

Pinkeye is a highly contagious disease affecting the eyes of sheep. Pinkeye may result from many different infective agents: Chlamydia, certain viruses, and mycoplasma. The disease will usually complete its course in three weeks in individual sheep. The use of eye medications containing antibiotics may be helpful in individual cases. There are no effective vaccines available, as the agent that causes pinkeye in sheep and goats is different from the one that causes it in cattle.

Read Infectious Keratoconjunctivitis (Pinkeye) =>

Pizzle Rot (sheath rot)

Pizzle rot is an infection in the sheath area of the ram. It is caused by the bacteria, Corynebacterium renale or one from that group. The other factor is high protein diets (>16 percent). Ammonia produced by the excess urea in the ram's urine can cause severe irritation and ulceration of the skin around the preputial opening. The debris from the ulcer form a crust which may block the opening to the prepuce. Pizzle rot can affect a ram's desire and ability to mate.

Plant poisoning

It is important to consider plant toxicities when diagnosing death losses. Many plants are toxic or potentially toxic to sheep. Some plants accumulate toxins during specific times of their growing cycle or after periods of environmental stress. The incidence of plant poisoning in livestock tends to increase when normal forages are scarce, causing animals to eat plants that they would not normally eat.

The signs of plant poisoning are as varied as the plants themselves and may mimic other diseases. Many poisonous plants cause sudden death. Some plants cause photosensitization (a severe skin reaction). Other poisonous plants affect the nervous system. Some plant poisonings can be treated if signs are recognized early. For many plant toxins, there are no treatments.

Pneumonia

(respiratory disease complex, pasteurellosis, shipping fever)

Pneumonia is second in importance to diseases of the digestive tract. Pneumonia is a respiratory complex with no single agent being solely responsible for the disease. The most common bacteria isolated from respiratory infections is Pasteurella haemolytica or Pasteurella multocida or both. Affected animals become depressed and go off feed. They may cough and show some respiratory distress. Temperatures are usually over 104°F. The disease may be acute with sudden deaths or take a course of several days. Pneumonia is treated with antibiotics. There is a vaccine for Pasteurella.

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM, CCN, polio, cerebrocortical necrosis)

Polioencephalomalacia is a disease of the central nervous system, caused by a vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency. Since the rumen manufactures B vitamins, polio is not caused by insufficient thiamine, but rather the inability to utilize it. The most common symptom of polio is blindness and star-gazing.

Polio most commonly occurs in lambs that are consuming high concentrate diets. Polio can also occur in sheep that consume plants that contain a thiamase inhibitor. Excessive use of amprolium (Corid) can cause polio. Polio symptoms mimic other neurological disease conditions, but a differential diagnosis can be made based on the animals' response to injections of vitamin B1.

Polyarthritis

Polyarthritis is an infectious disease of nursing lambs, recently weaned lambs, and feedlot lambs. Symptoms are stiffness, reluctance to move, depression, loss of body weight, and conjunctivitis. Clinically the disease is primarily characterized by stiffness and by conjunctivitis. Body temperatures over 104°F are common. Lambs can be treated with several different broad-spectrum antibiotics or tetracycline drugs.

Pregnancy Toxemia

(ketosis, twin lamb disease, lambing paralysis, hypoglycemia)

Pregnancy toxemia is a metabolic disease that affects ewes during late gestation. It most commonly affects ewes, overfat ewes, older ewes, and/or ewes carrying multiple fetuses. It is caused by an inadequate intake of energy during late pregnancy, when the majority of fetal growth is occurring.

Treatment is to increase the blood sugar supply to the body by administering glucose intravenously or propylene glycol or molasses orally. In extreme cases, removal of the fetuses is the only recourse to save the ewe and lambs.

Pregnancy toxemia can be prevented by providing adequate energy to ewes during late gestation, usually ½ to 1 lb. of grain per head per day, more for high producing ewes. Adequate feeder space is also necessary to ensure all ewes are able to consume enough feed.

Read Pregnancy Toxemia in Ewes and Does =>

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease of the central nervous system of mammals, spread by contact with saliva from an infected animal, usually through bites or scratches, abrasions, or open wounds in the skin. Domestic animals may become exposed during normal grazing or roaming. Sheep have symptoms similar to cattle, and sometimes vigorously pull their wool. Livestock and horse owners may decide to vaccinate their animals if they are often exposed to potentially rabid wild or domestic animals.

Generally, production animals, such as dairy cow herds and sheep flocks, are not vaccinated because the potential risks are usually lower than the annual costs of vaccination and because human contact with individual animals is low. Small groups of valuable purebred animals may be an exception. Producers who lease their animals for grazing or use their animals for exhibition should consider vaccinating. In recent years, a few states have required vaccination for rabies before an animal (including some livestock) can be exhibited publicly.

Rectal Prolapse

A rectal prolapse is protrusion of the rectal tissue through the exterior of the body. It usually begins as a small round area that sticks out when the lamb lays down or coughs. In extreme cases, the intestines can pass through the opening and the disease can be fatal. There are many predisposing factors to rectal prolapses, including genetics, short tail docks, coughing, weather, stress, and high concentrate diets.

Rectal prolapses tend to occur more in ewe lambs than wether lambs and more in black-faced sheep than white-faced sheep. It is a heritable trait, about 10 percent. Lambs on high concentrate diets are more prone. In fact, a link between ultra-short tail docking and concentrate feeding has been scientifically established. Usually, lambs with prolapsed rectums are prematurely slaughtered or sent to market. It is possible to repair a rectal prolapse by amputating the prolapsed part of the rectum. These lambs should not be kept for breeding.

Read Rectal prolapses: a complex problem with many contributing factors =>

Ringwomb

Ringwomb is when the cervix fails to dilate sufficiently to allow delivery of the lamb(s). While sometimes the cervix of affected ewes can be opened with gentle pressure or the injection of hormones, usually such efforts prove futile and a caesarian section to remove the lambs is the only option that will produce a successful outcome for both ewes and lambs. Unfortunately, little is known about the cause of ringworm and how to prevent it. There is some evidence to suggest that ringwomb has a genetic component.

Ringworm (club lamb fungus, wool rot, and lumpy wool)

Club lamb fungus is a highly contagious fungal infection of the skin of sheep. It is primarily a problem with show lambs that are frequently slick sheared. Club Lamb Fungus is caused by fungus of the genus Trichophyton. Infection occurs when the fungus invades the skin and hair (wool) follicles. Fungal spores are transmitted by contaminated clippers, blankets, combs, bedding, bunks, and pens. Lesions can appear anywhere, however, most are found on the head, neck, and back. The infection is susceptible to anti-fungal agents. Club lamb fungus causes a nasty ringworm infection in people.

Ryegrass staggers

Ryegrass staggers is a disease of grazing animals that causes muscle spasms, loss of muscle control and paralysis. It is caused by a group of toxins that accumulates in the leaf sheaths of perennial ryegrass. The toxins are produced by a native fungus called ryegrass endophyte, Neotyphodium lolii, that grows within the leaves, stems and seeds of perennial ryegrass. Sheep and cattle are most commonly affected but horses, alpaca. and deer are also susceptible.

Ryegrass staggers has not been recorded in goats. Affected animals have a stiff gait or are unable to walk. They may injure or kill themselves in transit. The toxins can induce high body temperatures thus animals will try to cool themselves. Younger animals tend to be worst affected. The symptoms of ryegrass staggers usually develop 7-14 days after livestock stock start grazing the toxic parts of the plant. Prolonged exposure to toxic pasture can lead to permanent neurological damage.

Scrapie

Scrapie is a degenerative, fatal disease affecting the central nervous system of sheep (and goats). The causative agent is believed to be a prion, a misshapen protein. The disease is spread via placenta, from the dam to her offspring and other lambs (and kids) that come into contact with her birthing fluids, placenta, and bedding soiled with birthing fluids. There is no treatment for scrapie. Affected animals always die.While the occurrence of scrapie in the U.S. sheep flock is low and getting lower all the time, it is a disease of regulatory concern. This is because scrapie is a member of a family of diseases called "transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TGE's), which also includes chronic wasting disease (in mule deer and elk), mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) and classic and new variant Creutzfeldt-Jacob's Disease (in humans).

Producers of breeding stock are encouraged to enrolled in the voluntary scrapie flock certification program, which after five years of scrapie-free monitoring, enables a flock to be certified "scrapie-free." Furthermore, while scrapie is not a genetic disease, a sheep's genetic make-up influences its susceptibility to scrapie if exposed to the infective agent. Therefore, sheep can be tested for scrapie resistance.

Read an Update on Scrapie =>

Scrotal hernia

A scrotal hernia is when the ram's intestines slip through the inguinal rings into the scrotum. The condition causes an enlargement of the scrotum. Scrotal hernias may be congenital or acquired. They are thought to be caused by trauma. While it may be possible to surgically repair a scrotal hernia, a more practical option would be harvest them for meat. Since heredity probably plays a role in the occurrence of a scrotal hernia, it is probably prudent to cull rams that sire lambs that develop hernias.

Septic pedal arthritis is a bacterial infection that usually gains entry to the distal interphalangeal (pedal) joint from an interdigital legion which then tracks across the joint to discharge above the coronary band. The foot is swollen with obvious widening of the interdigital space and a discharging sinus(es) above the coronary band. In chronic cases, there is considerable widening of the interdigital space and loss of hair around the coronary band. Chronic cases usually do not respond to antibiotic therapy. Digit amputation by a veterinarian is usually necessary.

Soremouth

(contagious ecthyma, scabby mouth, pustular dermatitis, orf)

Soremouth is the most common skin disease affecting sheep (and goats). It is a highly contagious viral infection that can also produce painful lesions in people. The virus causes scab formation on the skin, usually around the mouth, nostrils, eyes, mammary gland, and vulva. It first appears as tiny red nodules, usually at the junction of the lips. Treatment is usually unrewarding, though WD-40 has been advocated as a treatment. The disease will usually run its course in 1 to 4 weeks.

Effective vaccines are available. The vaccine is applied to a woolless area in the inside of the ear or under a leg where it cannot spread to the mouths of other animals. Once the vaccine is used on the premises, it should be continued yearly. Flocks that have not experienced soremouth should not vaccinate for soremouth since the vaccine introduces the virus to the farm.

Read Soremouth (orf) in sheep and goats =>

Spider Syndrome

(spider lamb disease, ovine hereditary chondrodysplasia)

Spider lamb syndrome is a genetic condition that causes lambs to have severe malformations of the skeletal system. These animals have very fine bone, crooked legs and a crooked spinal column, and a distinct lack of muscular development. They usually do not survive to full maturity.

The cause of the condition appears to be genetic alteration due to selection for extreme length and height in show sheep. The disease is found predominantly in black-faced lambs: 75% Suffolk and 25% Hampshire. In order to have this disease, lambs must inherit a recessive gene from each parent. Several labs offer genetic testing for spider lamb disease.

Urinary calculi (water belly, urolithiasis, calculosis)

Urinary calculi is a metabolic disease of wethers and rams characterized by the formation of calculi (stones) within the urinary tract. Blockage of the urethra by calculi causes retention of urine, abdominal pain, distention and rupture of the urethra or bladder. Left untreated, it can cause death.

The most common cause of urinary calculi is feeding rations with high phosphorus levels. Grain and oilseeds are usually high in phosphorus and low in calcium, whereas forages, especially legumes, have a much more desirable ratio. The ratio of calcium to phosphorus in the ration should be at least 2:1. Providing the proper balance of minerals in the ration is preferred to offering minerals free choice, since there is no guarantee animals will consume adequate amounts of free choice mineral.

Sheep rations should always include roughage, ideally long-stemmed forage. The addition of ammonium chloride (a urine acidifier) to the ration will aid in preventing urinary calculi. It is also important that animals have an ample supply of clean, potable water. The addition of salt to the ration will increase water intake and decrease stone formation.Ram lambs that are castrated at an early age are at increased risk for developing urinary calculi, as their urethras do not develop as fully. However, for animal welfare reasons, late castration is not advocated, as almost all cases of urinary calculi can be prevented with proper nutrition.

Read Urinary Calculi in Sheep and Goats =>

Uterine prolapse

A uterine prolapse is when the womb (uterus) is turned inside out and pushed through the birth canal by abdominal strainings of the ewe. It may occur immediately after lambing or several days later. A uterine prolapse is life-threatening. Before the prolapsed uterus can be put back into the ewe, the ewe's hindquarters should be raised. The uterus should be cleaned with a warm, soapy, disinfectant solution prior to replacement and should be replaced before the tissues become dry or chilled. Pouring water into the uterus will help to ensure that the tips of the horns are unfolded. Affected ewes should be given antibiotics and oxytocin. Unlike ewes that prolapse their vaginas, it is okay to keep a ewe that has prolapsed her uterus.

Vaginal Prolapse

Vaginal prolapses (protrusion of the vagina) are most commonly observed during the last month of pregnancy or shortly after lambing. Many factors have been implicated in the cause of vaginal prolapse, such as hormonal/metabolic imbalances, overfat/overthin body condition, bulky feeds, lack of exercise, dystocia in previous pregnancies, increased abdominal pressure and fetal burden. Prolapses often recur in subsequent pregnancies.

The exposed vagina of affected ewes should be washed with soapy disinfectant solution and forced back into the ewe. A bearing retainer or "spoon" can be inserted and secured in the ewe to prevent further prolapsing. There are harnesses that can be put on ewes to prevent further prolapses. Sutures are another option. Sutures must be removed in order for the ewe to lamb. The ewes can lamb with the spoon or harness in place, but it is better to remove them. Affected ewes and their offspring should probably not be kept in the flock for breeding animals due to the hereditary nature of the problem.

White muscle disease

(WMD, nutritional muscular dystrophy, nutritional myopathy, stiff lamb disease)

White muscle disease is a degeneration of the skeletal and cardiac muscles of lambs. It is caused by a deficiency of selenium, vitamin E, or both and can be a problem wherever selenium levels in the soil are low or the diet is deficient in selenium. Symptoms are stiffness of the hind legs with an arched back and tucked in flanks. Treatment is the administration of selenium and vitamin E by injection.

Feed rations should be evaluated to determine if they are providing adequate levels of selenium and vitamin E. If dietary levels of selenium are inadequate, lambs can be given an injection of selenium and vitamin E shortly at birth. Dietary supplementation of selenium is usually preferred to selenium injections. There is a narrow margin between selenium deficiency and selenium toxicity.

Read White Muscle Disease in Sheep and Goats =>

GO TO SHEEP DISEASE CLASSIFICATION (TABLE) =>

<== SHEEP 201 INDEX

Copyright© 2021. Sheep 101 and 201.